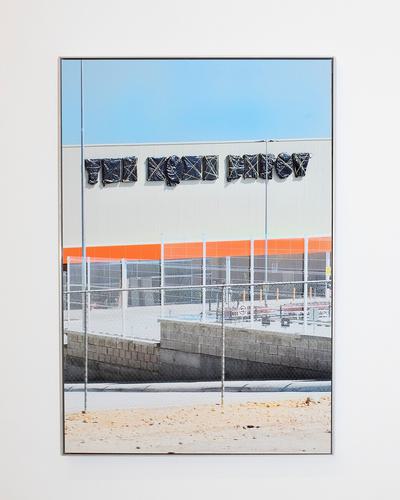

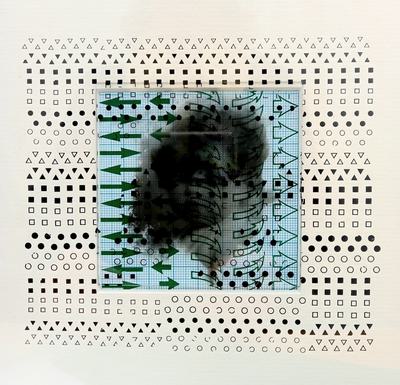

Artist Gallery

Discover over 12,000 artworks from over 1,000 selected artists and makers.

Highlights

Explore By Category

Gallery

Become a member

We support our members with: insurance, networks, space, opportunities, R&D awards, profiling, advice and mentoring.

Become a member